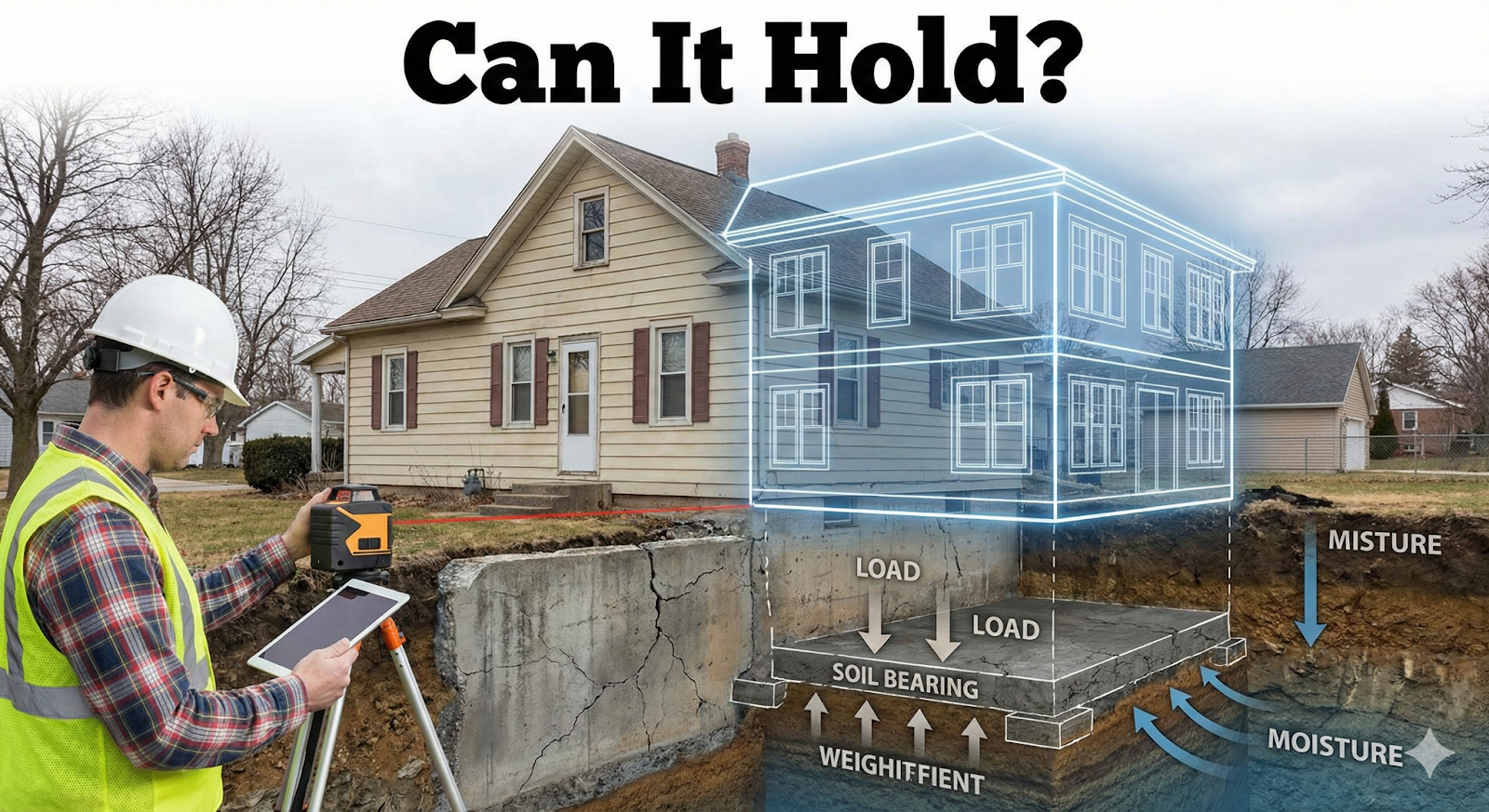

Although adding to a house may appear simple from the outside, the project’s success often depends on what lies below grade. Concrete in the ground is only one aspect of a foundation.

It is a system that shifts the weight of people, furniture, walls, and floors into soil that varies over time with the seasons and moisture.

The intended extension may require the current foundation to support more weight, connect to new footings, or withstand other stresses such as lateral movement and wind uplift. It takes a combination of measurement, document examination, and observation to determine whether it can achieve that.

If you are a homeowner planning to add a room addition to your house read this guide to anticipate risks and avoid unpleasant shocks once framing has started.

What to check before building my addition?

- Start With the Addition Loads, Not the Dream Layout

Converting the concept of an addition into actual forces that the building needs to support is the first stage. A two-story extension with a tiled bathroom, stone veneer, and substantial roof framework can weigh significantly more than a one-story family room with a basic roof. A foundation is more concerned with pounds per square foot and how those pounds land on bearing points than it is with square footage alone. Load pathways are also important. Existing walls may carry more weight to footings that were never designed to support it if new beams or joists are intended to land on them. Home addition planning also requires considering load intensity because roof span, beam size, and floor framing can concentrate weight on a few bearing lines instead of spreading it evenly. Thinking about the load early helps you ask the right questions during foundation inspection.

- Identify What Foundation Type You Actually Have

Different foundations respond differently to increased weight. A full basement with continuous footings and thick concrete walls has a different capacity and failure pattern than a crawl space foundation, a slab-on-grade foundation, or older pier-and-beam systems. Start by identifying access points, such as utility penetrations, crawl hatches, and basement stairwells, and then look at what now supports the house. Keep an eye out for indications of continuous footings, internal bearing pads, or beam-carrying piers. While internal load lines may rest on thickened sections or post-tension components, outside loads in slab homes are typically carried by the thickened edge or grade beam. Where to look next is indicated by the kind. An addition over a crawl space, for instance, might need to have its girder condition, moisture history, and pier spacing checked, while an addition hooking into a slab might need to have its edge thickened and reinforced.

- Use Visible Clues to Read Foundation Health

Look for signs that the foundation has been shifting, overstressed, or undermined by water before taking any measurements. Pattern is important, but internal cracks can tell a story. While masonry stair-step cracks, bigger fissures that offset, or cracks that open and shut with the seasons, can all be signs of soil movement or settlement, hairline shrinkage cracks in concrete are typical. Sloping floors, stuck windows and doors, or gaps between baseboards and flooring can all be signs of differential movement. Look out at the water draining. If the grade slopes toward the house or downspouts discharge near the foundation, the soil may become softer and lose its bearing power, especially during rainy seasons. Efflorescence, rusty steel, spalling concrete, or musty smells are signs of a long-term moist basement. Current deterioration or movement reduces the margin and may change the need for reinforcement, even though the foundation might theoretically be able to withstand more weight.

- Measure Levelness and Track Movement Over Time

Subtle settlements that become significant as more loads are added may be overlooked by a cursory walkthrough. Finding patterns can be done practically by measuring floor levelness. It is possible to determine whether one corner is lower than the others or whether the slope follows a line corresponding to an internal bearing wall using a long level, a laser level, or even a transparent tubing water level. The objective is to determine whether the structure is stable or actively changing, not to achieve perfection. It might be worthwhile to monitor for changes over a few weeks or months, particularly during a wet season, if you notice new gaps at trim joints, recent caulk separation, or fresh drywall cracks. Use a basic gauge to measure crack widths and take pictures with dates. Even if the new part is constructed appropriately, it may exacerbate movement if the foundation is still shifting, or cause a breach in the link between the old and new structures.

- Locate Footings and Estimate Their Size and Condition

Because footings distribute weights into the soil, they are frequently the weak point in foundations. You can often see the top of the footing in crawl spaces and basements, or you can estimate its width by looking where the wall flares at the base. You are searching for indications of undermining, a continuous bearing surface, and sufficient thickness. The load is no longer distributed evenly if the soil beneath the footing edge has washed away. Older homes may have footings that are shallow by today’s standards or that rest on fill instead of undisturbed soil. Determining the footing size in slab houses is more challenging without blueprints or small investigative cuts; nevertheless, visible control joints, plumbing penetrations, and the thickness of the garage slab border can offer hints.

Previous repairs, exposed rebar, or disintegrating concrete can all reduce effective strength. You should look into the footing proportions further with evidence or an expert evaluation if you are not convinced.

Building A Home Addition With Structural Confidence

Understanding loads, confirming what is already in place, and assessing the stability of the earth and the structure are all important factors in determining whether an existing foundation can support a new addition. A picture of capacity and risk can be constructed using visual cues, level measurements, footing examination, and drainage assessment. Records and authorization histories can fill in missing information, and the intended link between new and existing structures may influence load distribution and movement. It is safer to handle uncertainty as a design constraint rather than assuming the foundation can sustain more weight. A careful analysis up front protects the budget, the schedule, and the finished space’s long-term comfort.

Frequently Asked Questions:

- Does a home addition need a foundation?

Yes. Every structure requires a stable base to transfer its weight into the ground, but this doesn’t always mean pouring new concrete. If you are building “out” (increasing the footprint), you will need to pour new footings and walls. If you are building “up” (adding a second story), your existing foundation acts as the foundation for the addition. In this case, as the article explains, you must verify that the current footings are wide and stable enough to handle the extra pounds per square foot without sinking or cracking. - What are the warning signs that my foundation is too weak for an addition?

The article highlights several “visible clues” that suggest a foundation is already under stress. The most critical red flags are stair-step cracks in masonry (which indicate the house is settling unevenly), horizontal cracks in basement walls, and windows or doors that stick. morely, if you see signs of water damage—such as efflorescence (white powder) on concrete or rusty steel—the concrete may have weakened over time. If these patterns exist, the foundation likely needs repair or reinforcement before it can support new construction. - How does the type of foundation (Slab vs. Crawl Space) change the inspection process?

The inspection method depends heavily on access. For crawl spaces and basements, you can usually see the “flared” bottom of the wall to measure the footing width directly. For slab-on-grade homes, the article notes that inspection is harder because the critical load-bearing edges are hidden underground. In these cases, you may need to rely on “investigative cuts” (digging small test holes) or checking original blueprints to confirm the edge thickness and reinforcement before planning your load paths.